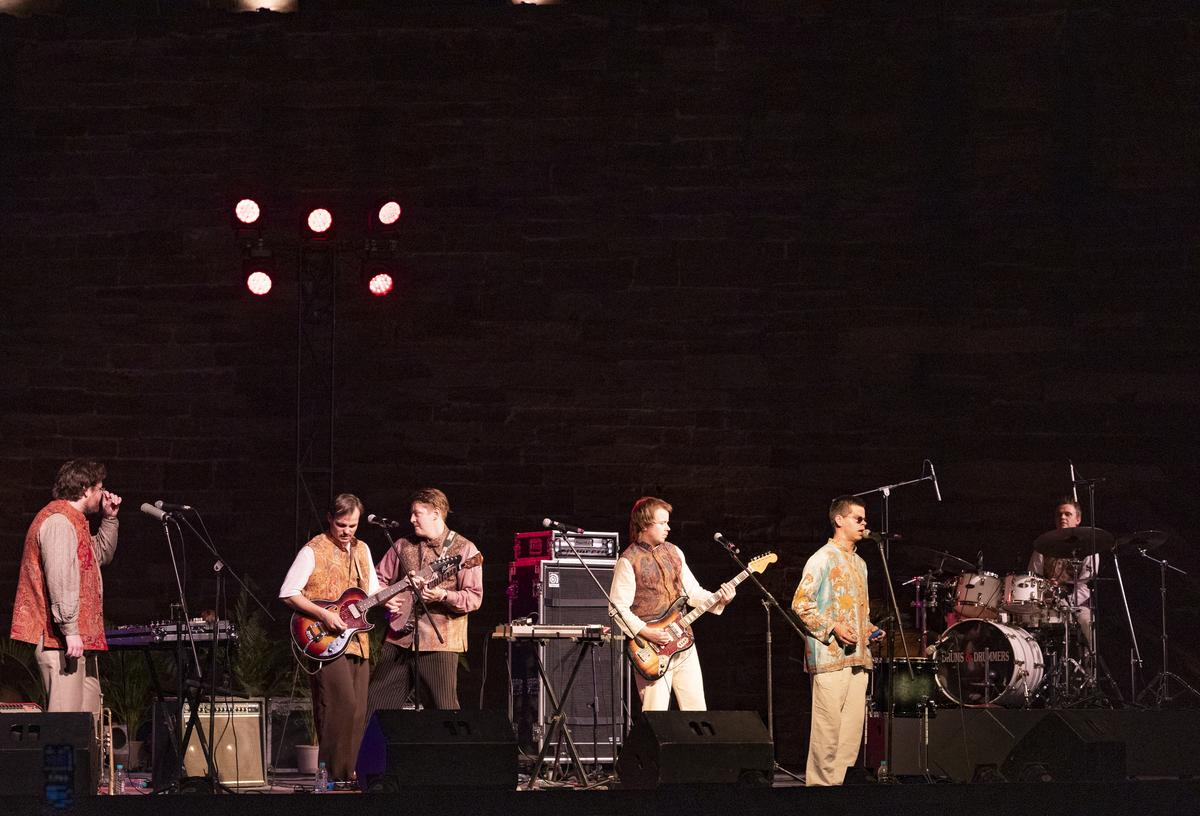

The collaboration between SAZ and Tarini Tripathi was one of the highlights of Jodhpur RIFF, 2024

| Photo Credit: Courtesy: Jodhpur RIFF/OJIO

One is made of beaten earth, the other of gourd. The overlapping origin stories of the ghatam and calabash more than peeked through in the musical conversations they made during the inaugural concert of Jodhpur RIFF. The instruments chatted like old friends, belying the fact that the musicians playing them were from different continents and had met just 10 minutes before getting on stage. Classical musician Giridhar Udupa and Congolese percussionist Elli Miller Maboungou demonstrated the essence of the fest.

The roots music festival, now in its 17th year, is known for bringing home music beyond classifications and divides. Urban-rural, classical-folk, vocal-instrumental, dance-music, local-international and other labels faded in the face of the experiences offered at the festival, with the picturesque settings (and grand entries and exits by the sun and moon) adding layers of impact.

Norwegian band Gabba presented Yoiks, the traditional singing style of the Sami people from northern Scandinavia.

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy: Jodhpur RIFF/OJIO

As always, this edition of the festival presented music of all kinds (exuberant, meditative, lyric-free, complex, subtle, direct) that was spoken, played, sung or even danced. While Norwegian band Gabba taught us about Yoiks, the traditional singing style of the Sami people from northern Scandinavia, the kharthal ensembles from Rajasthani folk communities displayed how playing rhythm could also be pure dance. That percussion can sing (and go solo) was proven time and again — with Natig Shirinov’s energetic performance and Sukkanya Ramgopal and team’s recital of rare Carnatic ragas on the ghatam. The similarities between Azerbaijan-based Natig’s rhythmic chanting and Indian konnakol could not be ignored.

Sukkanya Ramgopal and team’s recital of rare Carnatic ragas on the ghatam

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy: Jodhpur RIFF/OJIO

Estonian duo Puuluup had the audience torn between rolling on the ground, laughing, or joyously moving to their remarkable music interwoven with tunes from the talharpa (an instrument they’ve saved from the brink of extinction). The bandish of C.R. Vyas (presented by Anuja Zokarkar and team) heralded the rise of a crimson moon while Chandana Bala Kalyan’s Carnatic concert left a lingering mark on an emerging day. Music from the Manganiyars and Meghwals, Louis Mhlanga’s guitar recital, Kapila Venu’s Koodiyattam, Barnali Chattopadhayay’s musical exposition of Amir Khusrau’s poetry, Sumitra Das Goswami’s embodying mystic poetry, Gray by Silver’s reflective music and Emlyn’s powerful conjuring of the Indian Ocean — she hails from the Mauritius — the fare at this edition of Jodhpur RIFF was varied as ever, often left the audience making difficult choices.

The best of the interactive sessions (that included puppet shows, Tamasha, dance workshops and more) was a session titled ‘Why I do what I do’ in which five musicians from Rajasthani folk communities described how the arts intersect with their lives as women practitioners. The samples they presented of their work left one yearning to hear and know more, besides drawing many questions from a deeply-engaged audience.

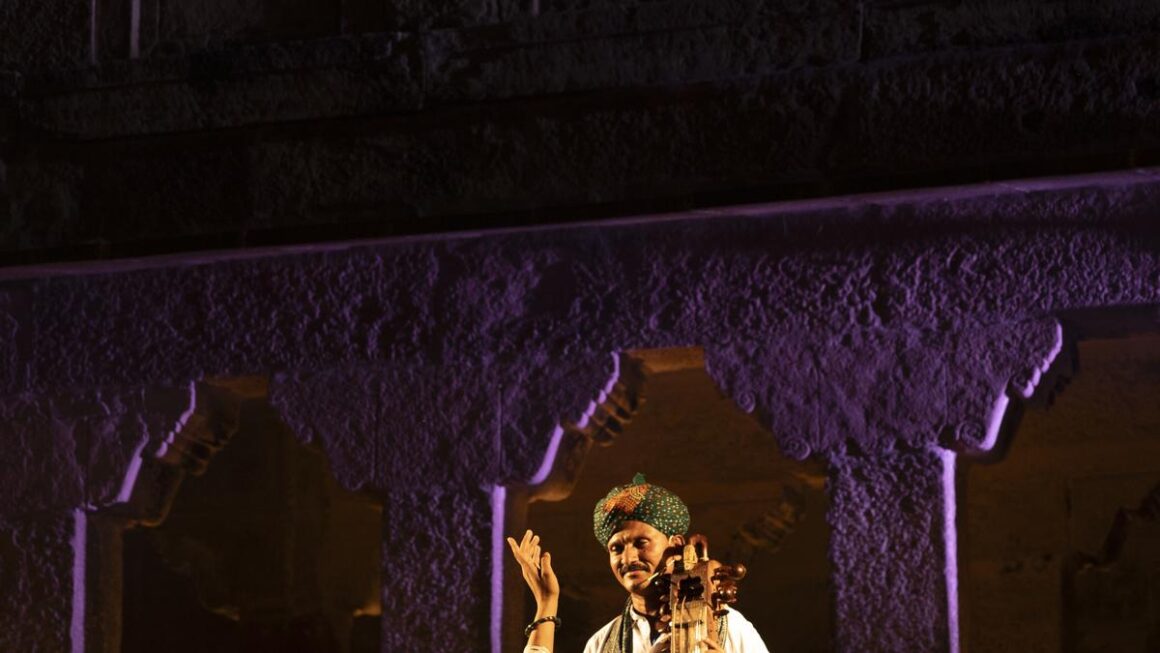

Marwar Malang, a sarangi jugalbandi, was curated by the festival director Divya Bhatia

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy: Jodhpur RIFF/OJIO

Of many collaborations that were presented at the festival, two stood out. In Marwar Malang, a sarangi jugalbandi curated by the festival director Divya Bhatia, Dilshad Khan’s classical sarangi produced a more refined sound and displayed classical music’s structured approach (with the instrument itself looking more spruced up) but the raw, throaty tunes from Asin Khan’s Sindhi sarangi unleashed a magnetism that defied resistance. The balanced manner in which the two sarangis wiped out the chasm of distance that could have stood between, spoke volumes about the musicianship of the two artistes and the way the festival has opened space for such musical interactions.

The other collaboration was between SAZ (that’s an acronym for Sadik, Asin and Zakir Khan – who play the dholak, Sindhi sarangi and khartal respectively) and Kathak dancer Tarini Tripathi. The beginnings of this collaboration was seen at last year’s festival edition, and it has grown into a more detailed exploration of making new forms from untapped artistic material within the artistes. Titled ‘Inayat — a duet for four,’ all four collaborators stepped out of their comfort zones in this evocative choreography. Asin Khan played a part in this movement sequence (while singing and playing the sarangi), Tarini and Zakir Khan sang (at different moments in the performance) and Sadik Khan recited poetry.

Sadik, Asin and Zakir Khan and Tarini Tripathi celebrated the beauty of artistic collaborations

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy: Jodhpur RIFF/OJIO

“In a conventional Kathak performance, the dance is at the centre and the music is fashioned around it but here, we are equal collaborators,” said Tarini, describing the process of making this work. “Our songs are based on stories more than on raags,” said Asin. The highlight of Inayat was the mature way in which folk and classical harmoniously co-existed, with neither upstaging the other.

Published – October 24, 2024 12:34 pm IST

Leave a Reply