Kendrick Lamar has a habit of making history through the most eclectic means.

Be it through documenting living amidst gang violence (good kid, m.A.A.d city), or celebrating and lamenting the African-American experience over jazz-infused beats (To Pimp A Butterfly), Lamar’s music is on the charts, on your mind, and in the conversation. His albums have spawned anthems chanted during “Black Lives Matter” protests, and have sealed their place in the pantheon of instant classics.

His third outing, ‘DAMN.’, sent him to number one with its hit ‘HUMBLE.’, and simultaneously won him a Pulitzer Prize for music, an accolade uncharted for rappers or even pop musicians. And once he was given the titles of “genius” and “hip-hop messiah”, his follow-up, “Mr. Morale and the Big Steppers”, saw him vigorously shaking off the glamour and responsibility that comes with them (“I am not your saviour / I find it just as difficult / to love thy neighbour”).

Mr. Morale was the last the world had heard of Lamar for nearly two years before he decided to make history once again.

In 2024, he engaged in a musical back-and-forth with Canadian pop-rap behemoth Drake. The feud got ugly — allegations were thrown, family members were insulted — yet it was unifying in its polarity, an unforgettable moment in Western pop culture.

Who won this beef? Ask any kid at a party screaming along to Lamar’s “Not Like Us”, a scathing call-out of certain alleged tendencies of Drake (“Certified lover-boy? / Certified pedophile.”)

The beef produced tracks such as “euphoria” (“I hate the way that you walk / the way that you talk / I hate the way that you dress”), which led to the easy conclusion that the current leg of Lamar’s career is fuelled by pure, unadulterated hatred.

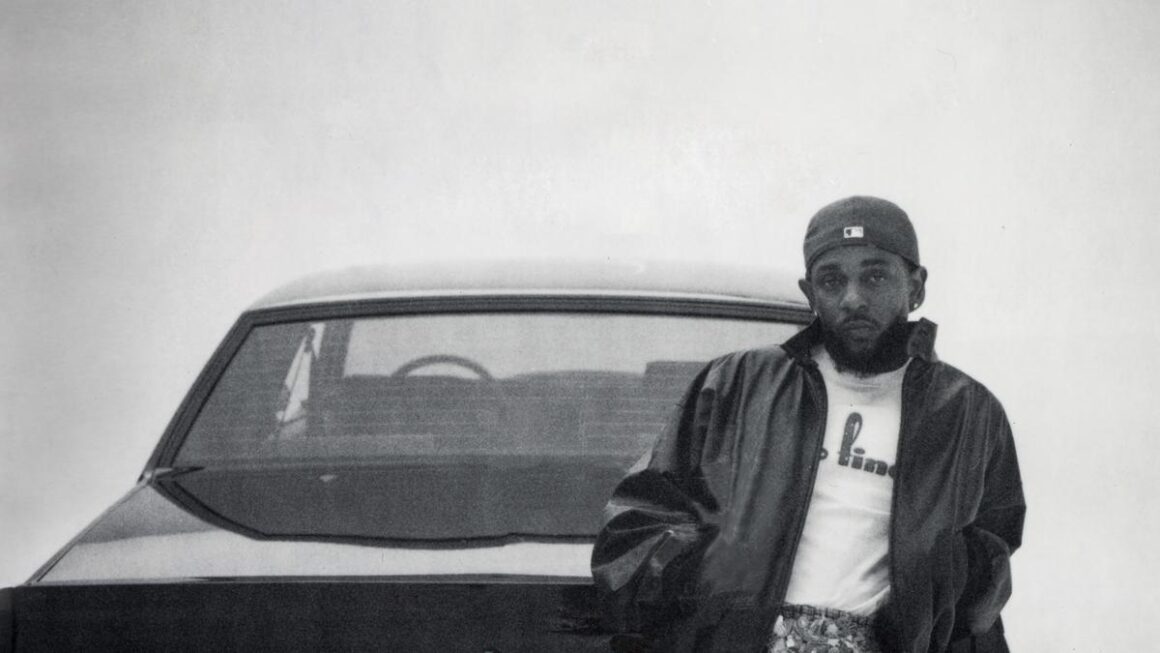

Kendrick Lamar performs at Coachella Music & Arts Festival at the Empire Polo Club, April 16, 2017, in Indio, Calif. (Photo by Amy Harris/Invision/AP, File)

| Photo Credit:

Amy Harris

Or so it would seem. When Lamar surprise-dropped his latest album “GNX”, on a random Friday, listeners expected a continuation of this energy. But GNX is not an extension of this victory lap. Rather, it’s the heavy sigh after, a contemplation of the hurdles, effort, and drive it took to get to the finish line.

The opener, “wacced out murals,” is a stoic reflection of Kendrick’s psyche in a post-Mr.Morale world. Mr. Morale and GNX are, at their core, confrontational albums. The difference is that this confrontation is now directed towards Lamar’s naysayers (which now includes hip hop legends Lil Wayne and Snoop Dogg), cultural appropriators, and perhaps even the skeptical listener.

“I deserve it all,” he repeats on “man at the garden”, justifying this claim diligently in every verse, a stark contradiction to his prior attempts to humanise himself. And amidst the cutting confidence and sterile production, you almost find yourself believing this God-like self-projection.

And then you get hit with the centerpiece of the album, “reincarnated”.

Every Lamar album lends a track or two to story-heavy writing exercises (see: “Sing About Me, I’m Dying of Thirst”) which end up revealing more about Lamar himself than any of his subjects.

As he lyrically waltzes through the lives of Black musicians such as John Lee Hooker and Dinah Washington, he frames his musical talent as powerful — both in its ability to uplift and topple. The song, which interestingly samples 2Pac’s “Made N****z”, narratively concludes with Kendrick speaking to God, likening himself and these musicians to fallen angels, and vowing to use his gift to spread light.

The tracklist, in its lower-case sheen and crisp 44-minute runtime, contains more such cracks in the facade; peeks into the love — for his city, culture, people, and craft – that has always driven Lamar’s music. Besides the explicit love letter to his city, “dodger blue”, even the more vengeful, potential hits of the record (“squabble up”, “tv off”, “hey now”) are embellished with the bass-heavy bounce associated with Lamar’s hometown, Los Angeles. The other artists featured on the record are almost exclusively from the West Coast, and pitch in unforgettable verses (see: Hitta J3 and YoungThreat on the title track).

Lamar’s roots have always held a place in his lyrics, but this is perhaps his first album in which they manifest so heavily in the sonics.

“heart pt.6” is another challenge to Lamar’s curated exterior, an ode to his peers at his previous record label, Top Dawg Entertainment, and his love for them that still dictates his business decisions (“If that’s your family / then handle it as such”).

“luther” and “gloria”, which prominently feature frequent collaborator SZA, are straight-up love songs. However, even amidst a lush, sentimental cut like luther, Lamar’s vitriol finds its way (“If the world was mine / I’d take your enemies to God / Introduce them to that light / hit ‘em strictly with that fire”).

gloria is a slow jam that lays out the highs and lows, the division of blame, and the love that remains in his relationship — not with his fiancee and high school sweetheart Whitney Alford, but his pen.

GNX, in its constant sonic movement, frequently toes the line between the man who gave himself the title “Pulitzer Kenny” and the human beneath it, who lives with the consequences of riling up love, hatred, and envy in millions. Where his previous albums have explored themes of fear, protest, inquisition, and acceptance, GNX runs on self-preservation.

GNX is streaming on major music platforms.

Published – November 29, 2024 06:35 pm IST

Leave a Reply