The Music Academy’s 2024 academic conference featured a lec-dem on ragas Abheri and Ahari, and a percussion perspective of accompanying a raga.

The seventh day of The Music Academy’s annual academic conference featured a lecture on ‘Mysterious Medieval Transformations – Ragas Abheri and Ahari’ by K. Srilatha,

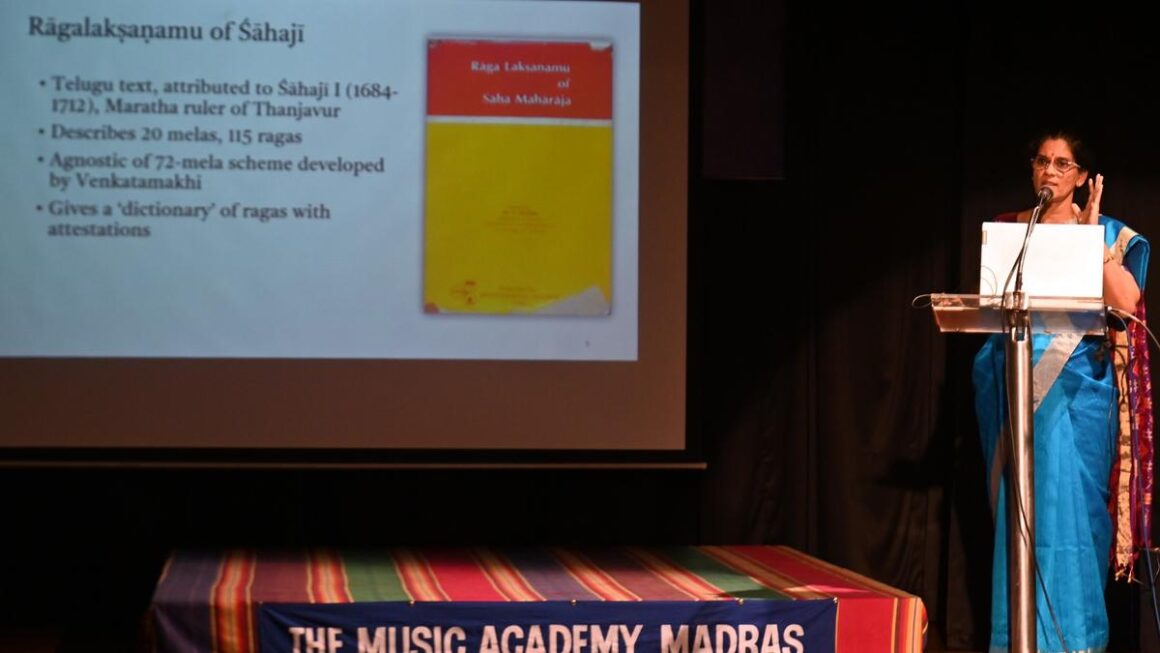

She opened the lecture with a history of the classification of these ragas, starting from the 16th century Svaramela Kalanidhi. This text lists both Abheri and Ahari in the Ahari mela (with the notes of present-day Keeravani). Subsequent works in the 17th and 18th centuries beginning with Thanjavur Maharaja Sahaji’s Raga Lakshanamu, place both ragas in the Bhairavi mela (present-day Natabhairavi).

Raga Lakshanamu records the details of 20 different melas and 115 ragas categorised within those melas along with their notes and common phrases. Sahaji also gives details about the nature of different phrases. It was previously unknown where Sahaji drew his knowledge of raga lakshana from — the oral tradition or written.

Here, Srilatha introduced the Gita manuscripts from Thanjavur Maharaja Serfoji’s Sarasvati Mahal Library. The manuscripts give the notation of older compositions along with annotations that give information about raga lakshana. These annotations describe the mela of a raga using a base well-known mela (e.g. Varali, Gaula, Bhairavi) and modifications (use a higher ‘ni’). Abheri is placed in the Ahari mela which is described as the Bhairavi mela with the ‘ni’ of Gaula (i.e. present-day Kiravani).

She then shared her rendition of a Gita in Abheri, which she had reconstructed from the Gita manuscripts. It has characteristic phrases of (then) Abheri-like jumps from ‘pa’ to ‘sa’ and a ‘sa ni pa’ in descent. This Gita also exists in a similar form in Subbarama Dikshitar’s Sangita Sampradaya Pradarshini (1904) though it is placed in the same mela as Bhairavi.

Srilatha gave examples of annotations for several other ragas in the Gita manuscripts, noting that it was a more practical and efficient method than using arcane svarasthana names. She showed that for most ragas in the Raga Lakshanamu, they matched exactly with the annotations of the Gita manuscripts. Exact phrases from those manuscripts were used in Sahaji’s descriptions. This makes it very likely that those manuscripts were the source of Sahaji’s raga lakshanas. She also gave examples of Gita annotations missing the expected modifier to the base mela, due to inconsistencies between manuscripts or the fragility of the palm leaf medium.

In the case of Abheri and Ahari, Sahaji placed both ragas in the Bhairavi mela. All subsequent texts seem to follow the Raga Lakshanamu’s example, including the Sangita Sampradaya Pradarshini. She concluded that this shows that these ragas likely changed because of inconsistencies in the Gita manuscripts Sahaji used or an error in transmission by Sahaji.

The expert committee pointed out the similarities between Raga Lakshanamu and Tulaja’s Sangita Saramrta. The latter is a larger text and broader in scope, but the overlapping ragas have largely similar descriptions with some differences, indicating that they both likely drew from similar Gita sources. It was also noted that Bhairavi could have had multiple versions in vogue simultaneously, e.g. the 17th century text Sangita Sudha mentioning chatusruti (middle) dhaivata in Bhairavi (then Bhairavi was only listed with the shuddha dhaivatam (lower)).

Sangita Kalanidhi-designate T.M. Krishna summarised the session and highlighted the different ways lakshana (written tradition) has been constructed, either based on previous lakshana or on lakshya (oral tradition). Given the practical annotations in the Gita text, Sahaji seems to have followed the latter process. He put forth the idea that anya, as conceived today, is a restrictive concept that does not encapsulate the scope for variability of raga presentation.

Arun Prakash, Brindha Manickavasakan and N. Madan Mohan

| Photo Credit:

K. Pichumani

The second morning session ‘Accompanying a raga – A percussive perspective’ was led by mridangam exponent K. Arun Prakash. He was supported by Brindha Manickavasakan and N. Madan Mohan on the vocals and violin, respectively.

Arun Prakash (seated in the middle) started by briefly speaking about raga being the essence of Carnatic music. The lec-dem was entirely made up of kirtana renditions, presented live by the musicians, along with Arun Prakash’s insights during and after each rendition.

The first two kirtanas were in raga Kannada — ‘Ninnada nela’ (Adi tala) and ‘Sri Matrubhutam’ (Misra Chapu tala). Arun Prakash’s different approaches to accompanying the two songs were immediately clear. He mentioned how the gait and spread of syllables in ‘Sri matrubhutam’ are very different from that of ‘Ninnada mela’. He was also quick to note that the differences between the two approaches were not simply because of the tala and kalapramana differences, but because of the sound of the raga itself.

This lec-dem was one that was full of vocal, emotional appreciation from the audience. One such moment that prompted this was how Arun Prakash beautifully played for the last word of Sri Matrubhutam’s charanam, ‘Paramasivam’. There was such sensitivity in how the sahitya had been internalised by the musician that one could almost hear pa ra ma si vam played on the mridangam.

Next was Muthuswami Dikshitar’s ‘Chetasri Balakrishnam’ in raga Dwijavanthi. This was yet another example of Arun Prakash’s “less is more” approach to accompanying this type of song. He even chose not to play for the entire first line! Instead opting to let the voice, violin and tambura resonate before entering the composition himself.

One common feature of the lec-dem was Arun Prakash highlighting beautiful landing notes of certain lines in compositions (Vandita Charanam in ‘Sri matrubhutam’, Vatapatra Shayanam in ‘Chetasri’). This was sometimes highlighted by silence in the mridangam playing.

What followed was a brisk rendition of ‘Thaye Tripura Sundari’ in raga Suddha Saveri. This was an almost polar opposite sound to ‘Chetasri’ and revealed that all types of tones are beautiful and can be played appropriately. The accompaniment was bright and strong (the term vittu vaasikardhu was used), with a focus on the arithmetic in the composition’s structure, particularly during the chittaswara.

The boldest choice of the lec-dem was to then present Syama Sastri’s Bhairavi swarajathi in its entirety. This section of the lec-dem crystallised a lot of Arun Prakash’s ideas of accompaniment. He spoke about the compositional structure and raga-inspiring accompaniment as opposed to tala. One beautiful idea was the notion of “composing accompaniment” to a song, which requires deep internalisation of the structure, raga, sahitya, tala and how all these come together. This was later endorsed enthusiastically by Krishna. A notable aspect of the accompaniment (volume, speed etc.) was how it mirrored the tone of the swarajathi as it progressed from low shadja to high shadja.

T.M. Krishna was appreciative in his summative remarks and raised questions about what is expected of mridangam artistes on the performance stage. Expectations such as speed and mathematical acumen may overshadow sensitivity and porutham (appropriateness). The lec-dem closed with a sentiment that all of us — musicians and rasikas — have a shared responsibility to create the illusion that is art.

Published – December 25, 2024 11:29 am IST

Leave a Reply