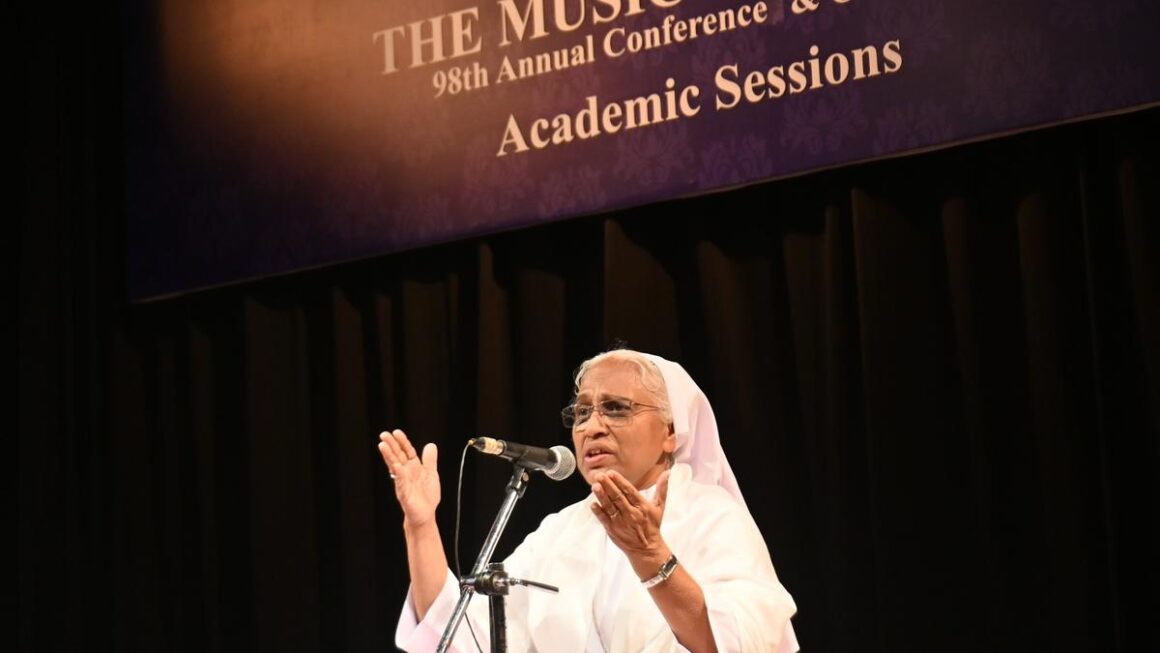

The first lec dem on Day 14 of The Music Academy’s academic sessions was by Sister Bastian ‘Sarva samarasa kirtanaigalum sanmargak kirtanaigalum’. She discussed the profound contributions of Vallalar, who is believed to have learned and composed 6,000 verses, embedding his life experiences within them. He attributed his compositions to divine intervention. Vallalar’s song ‘Ennakum unnakum’ reflects this divine connection.

Despite being written 2000 years ago, Vallalar’s compositions remain relevant today. Vallalar was not only a poet but also a doctor, educationalist, and reformer. Known for his powerful voice, he often sang at high pitches. He deeply admired and drew inspiration from figures like Vedanayagam Pillai and Sundarar, one of the 63 Alwars. Vallalar’s songs reject caste and creed and encourage universal love.

Vidwan T.M. Krishna reflected on the unusual pairing of Vallalar and Vedanayagam Pillai, noting that although they led different lives, their philosophies shared common ground. Krishna observed their distinct yet parallel journeys in the search (‘thedal’) for god. Drawing comparisons between Vallalar and Narayana Guru, he admired their ability to integrate social activism with spiritual teachings. Krishna recounted his introduction to Vallalar’s compositions during concerts in Vadaloor and mentioned other musicians who tuned Vallalar’s works, including Alathur Venkatesha Iyer and Guruvayur Ponnamal.

He emphasised the role of Thiruvaduthurai Adheenam in providing a space for classical music, transcending barriers of caste, creed, and religion, likening it to the Madras Music Academy of its time. Krishna cited Arthur Popely’s 1933 writings, which noted that many Christian songs had been tuned to Carnatic ragas like Desiyatodi, Shuddhadesi, and Saindhavi. Krishna also shared an interesting anecdote about the song ‘Iraivanidam Kaiyendagal,’ popular in namasankeerthanam, which was composed by Nagore Haneefa. This song is rendered both as an Islamic and a Hindu devotional song. This example underscores the transcendent nature of Vallalar and Vedanayagam Pillai’s philosophies, proving that spiritual expression cannot be confined to any single tradition or identity.

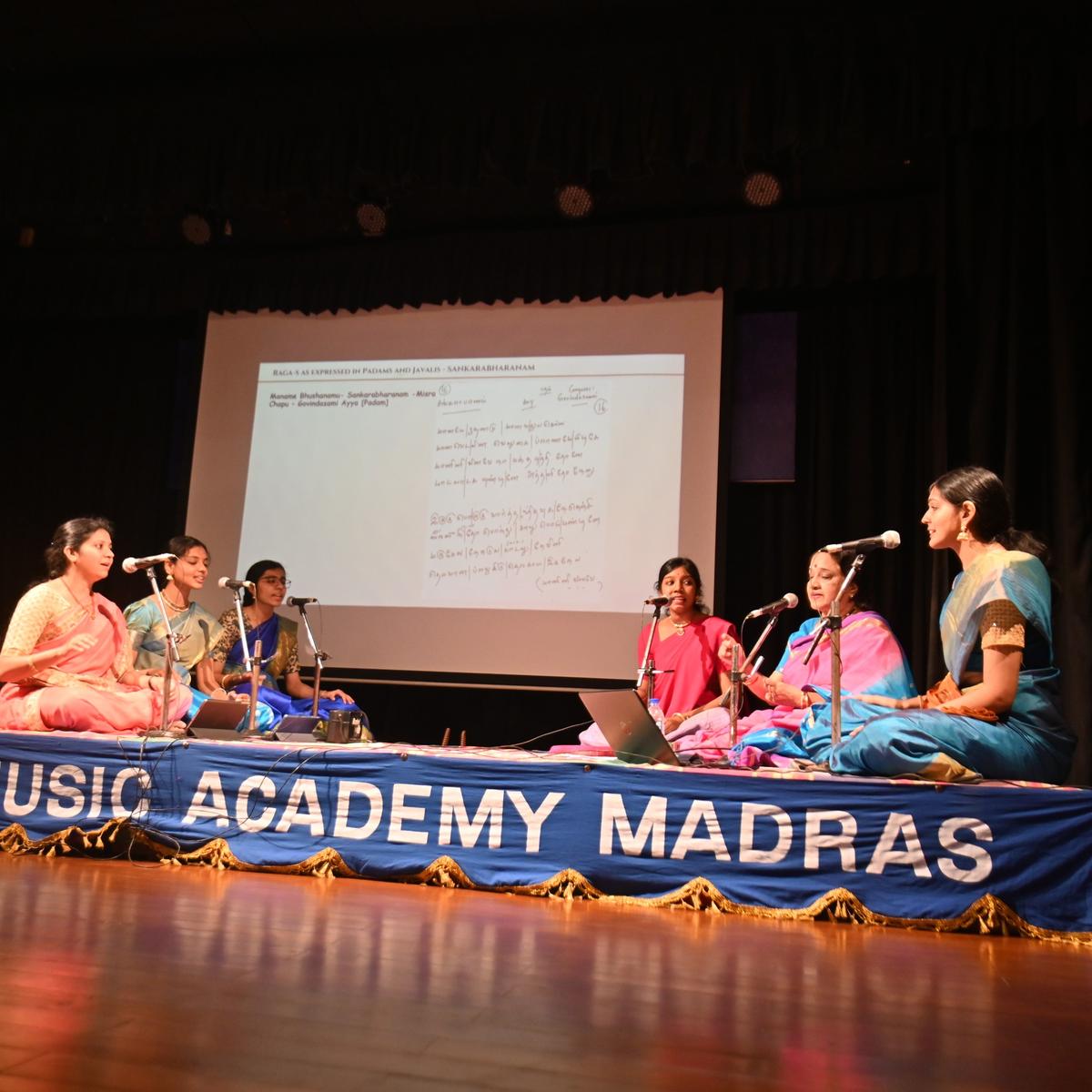

Geetha Raja and her disciples

| Photo Credit:

K. Pichumani

The second lec-dem was by Sangita Kala Acharya awardee Geetha Raja along with a few of her disciples on the topic ‘Ragas as expressed in padams and javalis. Her session offered a deep dive into the significance of padams and javalis in Carnatic music, particularly as expressed through the Dhanammal family tradition. She recounted her experience of learning under the inimitable T.Brinda, emphasising the profound impact of this training on her understanding of ragas.

Geetha explained that padams are distinguished by their long sancharas (melodic movements), especially in vilamba kala (slow tempo), and are traditionally set to talas such as Rupaka, Triputa and Misra Chapu. The beauty of padams lies in their complexity, and they cannot be precisely notated due to their intricate gamakas (ornamentations). Hence, padams are passed down through oral tradition.

In contrast, Geetha noted that javalis are faster-paced compositions, but with the same expressive quality as padams. Moving through select ragas, she performed and analysed several compositions to illustrate these concepts. She started with the Sankarabharam padam ‘Maname bhushanamu’, set in Misra Chapu tala, composed by Govindasami Ayya. Like most padams, it began with the anupallavi. Geetha demonstrated a raga alapana by replacing lyrics of the padam with syllables such as ‘Tha dha ri na’, a technique used in alapanas. She pointed out the connection between the varnamettu of this padam and that found in other compositions such as ‘Manasu swadhinamaina’ and ‘Mahalakshmi jaganmatha’.

Next, Geetha moved to raga Bhairavi, singing the Kshetrayya padam ‘Rama rama pranasakhi’ (Adi tala). She highlighted its unique eduppu (starting point) that occurs five counts after the ‘samam’ which she referred to as five ‘maatharais’. This padam’s distinctive use of nishadam was compared to the composition ‘Balagopala’ by Muthuswami Dikshithar. She further explained the unconventional use of specific melodic phrases in ‘Yela radayane’, a javali in Bhairavi, where T.M. Krishna pointed out the substitution of ‘P m g r S’ for the typical ‘p G r S’ in the raga’s phrasing in similar contexts.

Geetha concluded with a javali in Paras, ‘Smara sundaranguni’, composed by Dharmapuri Subbarayar, highlighting the unusual use of prati madhyamam in its ‘d p p m’ phrase in the charanams, which does not adhere strictly to the raga’s traditional grammar.

The session also included intriguing discussions among experts, including Ritha Rajan, who praised the notation of Kshetrayya padams by Sangita Kalanidhi Vedavalli and spoke about the probable influence of thevarams on the eduppus of padams. She added that ‘Rama rama pranasakhi’ might have possibly been set to tune taking inspiration from the composition ‘Tanayuni brova’. Ritha also mentioned that ‘Rama rama pranasakhi’ is sung in the raga Ahiri and Jhampa tala in the Andhra traditions. Sangita Kala Acharya Suguna Varadachari pointed out how she learnt the javali ‘Nee maatale mayanura’ in Misra Chapu compared to the popular Adi tala version and explained the evolving nature of Javali renditions over time.

In his summary, T.M. Krishna highlighted how the Dhanammal family transformed the compositions they inherited, emphasising their creative flexibility in challenging the grammatical boundaries of ragas using the example of the composition of Subbarama Dikshitar ‘Kanthimathi’. He also highlighted a few key phrases found in the padams presented earlier – the unusual Thookal madhyamam in ‘Bala vinave’ which yet sounded like authentic Kamboji – thereby putting forth a question to ponder upon in the minds of current-day musicians, “Do we box ourselves within the established strict grammar of ragas?”

On the whole, the presentation provided valuable insights on Padams and Javalis as a form. Her lecture contributed significantly to the ongoing discourse on Carnatic music, enriching the understanding of Padams and Javalis and their meanings, and shedding light on the musical legacy of the Dhanammal family.

Published – January 10, 2025 06:06 pm IST

Leave a Reply