Day 9 of the academic sessions at The Music Academy started off with a captivating lec dem by Nedumbally Ram Mohan and Meera Ram Mohan on ‘Abhinaya Sangeetam of Kathakali: The Blend of Raga and Bhava’. The session explored the unique musical tradition of Kathakali, focusing on its distinct use of ragas, emotional expression (bhava), and structural frameworks. They emphasised that Kathakali music differs significantly from Carnatic music, both in its melodic and emotive approaches.

They began by discussing how certain ragas in Kathakali evoke specific emotions and serve dramatic purposes. For instance, Paadi, a janya of Maya Malavagowla, is used to depict villainous characters in romantic padas like Duryodhana and Ravana. Ram Mohan demonstrated a four-kalai padam, typically employed in yuddha (battle) sequences or to convey veera rasa (heroism). The presentation also highlighted indigenous ragas such as Indalam, and Kanakurunji. The latter is often used to portray helplessness, exemplified in scenes such as Kunti asking for help from Bakasura. The presenters explained that Kathakali compositions primarily consist of padams and shlokas, with talas playing a crucial role in shaping emotional depth.

The Mohans demonstrated raga Dwijavanti, often associated with pleading, which acquires a different emotional tone when rendered in madhyama sruti. Similarly, Punnagavarali conveys sorrow, as in Sita’s lament to Hanuman, but transforms into a more devotional mood when sung in madhyama sruti, as demonstrated by Ram Mohan while singing a soliloquy from the story of Sudhama and Krishna. He elaborated on how shifts in sthayi (octaves) alter moods — Bhairavi, for example, evokes romance in madhyama sthayi but helplessness in higher octaves. Ragas such as Sahana, Senchuruti, and Begada were also analysed for their emotive versatility.

The session emphasised that Kathakali music is applied music, deeply tied to dramatic context rather than standalone performance. Ram Mohan demonstrated how tonal stress and variations must synchronise with the movements of the actors. He illustrated it with Bhima’s killing of Duryodhana using Saranga raga.

The interplay of sthayi bhava (dominant emotion) and sanchari bhava (transitory emotions) was also discussed, showcasing how Kathakali integrates music and drama seamlessly.

During the Q and A session, a comment was also made from a member of executive committee about the perception that singing for dance is inferior to proscenium singing, emphasising the need to change such attitudes. V. Sriram remarked that K.V. Narayanaswamy’s practice of singing phrases in both lower and higher octaves might have been influenced by Kathakali music, as demonstrated by the presenters. Vidwan T.M. Krishna concluded the session by highlighting the importance of emotion and tonality in Kathakali music. He drew attention to the role of non-musical tones in dramatisation, saying that there is also emotion in the way the non-musical tones are used. He also noted the density of the sahitya, where for instance, scenes expressing veera rasa (heroism) would have denser lyrics, while sringara rasa (romance) would feature sparser text, paralleling it to human speech patterns where anger produces rapid, intense speech. Krishna also argued that Kathakali ragas possess their own lakshana (structure) and lakshya (expression) independent of Carnatic classifications. He urged listeners to stop associating Kathakali ragas with dominant Carnatic equivalents and to recognise their distinct identity. Krishna also noted that the syllables of the text did not match the beat of the tala, to which Ram Mohan explained that there are markers and there are beginning and end points, but in between, the syllable / text can be sung in a free flow manner because the music is improvised. An audience member requested Krishna to present a Kathakali padam in one of his concerts, to which he responded thoughtfully, emphasising the importance of respecting the aesthetic framework of Kathakali rather than imposing external interpretations.

This session offered valuable insights into the distinct musical and dramatic world of Kathakali, highlighting its unique grammar, emotive depth, and cultural significance. It also sparked critical reflections on preserving tradition while appreciating cross-genre influences.

Amrita Murali

| Photo Credit:

K. Pichumani

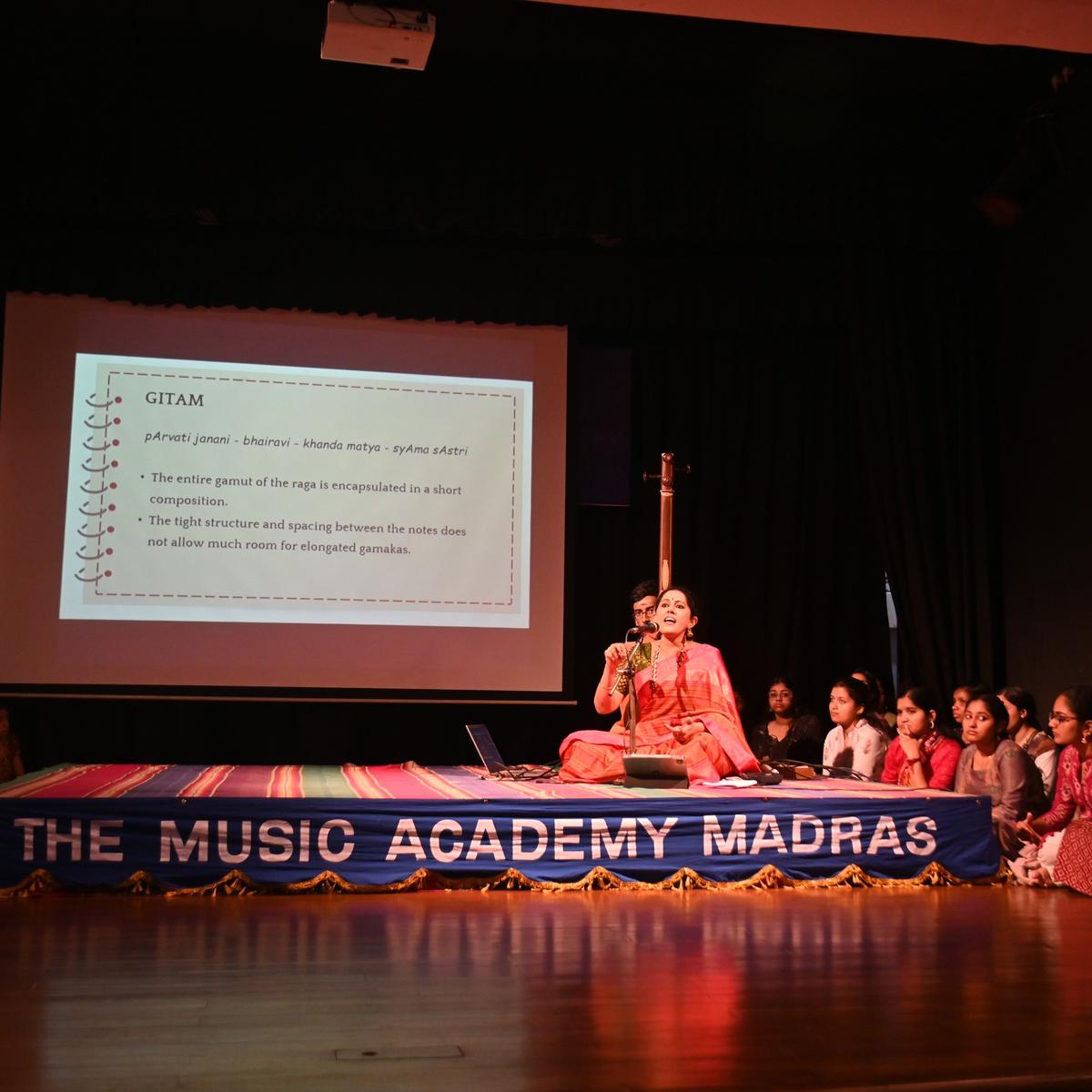

Amrita Murali on different compositional forms

The second session featured a lec dem by vidushi Amrita Murali on ‘Raga’s changing nature across compositional forms’. She explored how the aesthetics of a raga evolve and adapt when expressed through different compositional structures. Highlighting key forms such as Geetams, Varnams, Swarajatis, Kritis, Padams, Javalis, and Tillanas, Amrita provided detailed insights into their unique characteristics and treatment of ragas.

Amrita began by discussing Geetams, which encapsulate the entire essence of a raga within a compact framework. Using ‘Parvati Janani’ in Bhairavi (Khanda Matya tala) by Syama Sastri, she demonstrated how the composition starts in the tara sthayi shadjam, leaving no space between notes and embedding jharus within the first two lines. This tight structure captures the raga’s essence in a concise manner. She then shifted focus to Varnams, emphasising their ability to highlight rare phrases and intricate patterns. Analysing the magnum opus — Viribhoni Varnam by Pachimiriyam Adiappa Iyer in Bhairavi, she explained how unique phrases like ‘ndmgr; and ‘ngrndm’ define the raga. She also noted that the fourth chittaswaram and anubandham, no longer sung today, provide additional dimensions to the composition. Amrita illustrated how leaving out anuswaras can dilute the raga’s identity, stressing the importance of preserving traditional nuances.

Moving to Swarajatis, Amrita examined Syama Sastri’s Bhairavi and Yadukula Kamboji compositions, pointing out how arohana krama offer ideas for raga development. She highlighted the absence of the ‘rmg,S’ phrase in the Yadukula Kamboji Swarajati, which still effectively conveys the raga’s flavour. The session then delved into kritis, where sangatis drive a raga’s progression. Amrita observed that many of Muthuswami Dikshitar’s compositions, defy linear progressions. In ‘Balagopala’ in Bhairavi, she emphasised how lyrical content influences phrasing — heavier tones for words such as Drona and Duryodhana and softer jharu transitions for Draupadi. She also highlighted Begada in Tyagaraja’s ‘Nadopasana’, noting that phrases such as ‘vishwamella’ and ‘vidhulu velasiri o manasa nadopasana’ have remained intact, retaining the raga’s essence.

Amrita then explored Padams, focusing on ‘Indendu vachchithina’ in Surutti, where hints of sadharana gandharam enrich the melodic texture. She observed how Padams avoid repetitive dhatu prayogas , preserving freshness in rendition. Discussing Javalis, she pointed out their adaptability to different talas, which can alter a raga’s feel. Turning to Tillanas, Amrita highlighted Chinnayya’s Begada Tillana, showcasing phrases like ‘dpd grg’ and’ rggmpdp’, which are rarely sung today.

Amrita concluded with T. Vishwanathan’s version of Janaro in Khamas, celebrating its use of kakali nishadam. Sangita Kalanidhi designate T.M. Krishna summed up the session. He cited the Kalyani Geetam ‘Kamalajadala’ as an example where phrases like’ ddd ggg’ now not considered Kalyani at all, still persist in older compositions. He discussed the influence of tempo (kalapramanam) on gamakas, explaining that certain gamakas have a speed threshold. Krishna raised a critical question — whether all ragas can be transformed into all types of compositions. Referring to Shaji’s writings, he noted that Ghana ragas were traditionally chosen for tana varnams because their melodic nature synchronises with the aesthetic form of the tana varnams. Yet Bhairavi, which is not classified as a Ghana raga, has produced the most celebrated tana varnams.

Published – December 29, 2024 11:54 pm IST

Leave a Reply