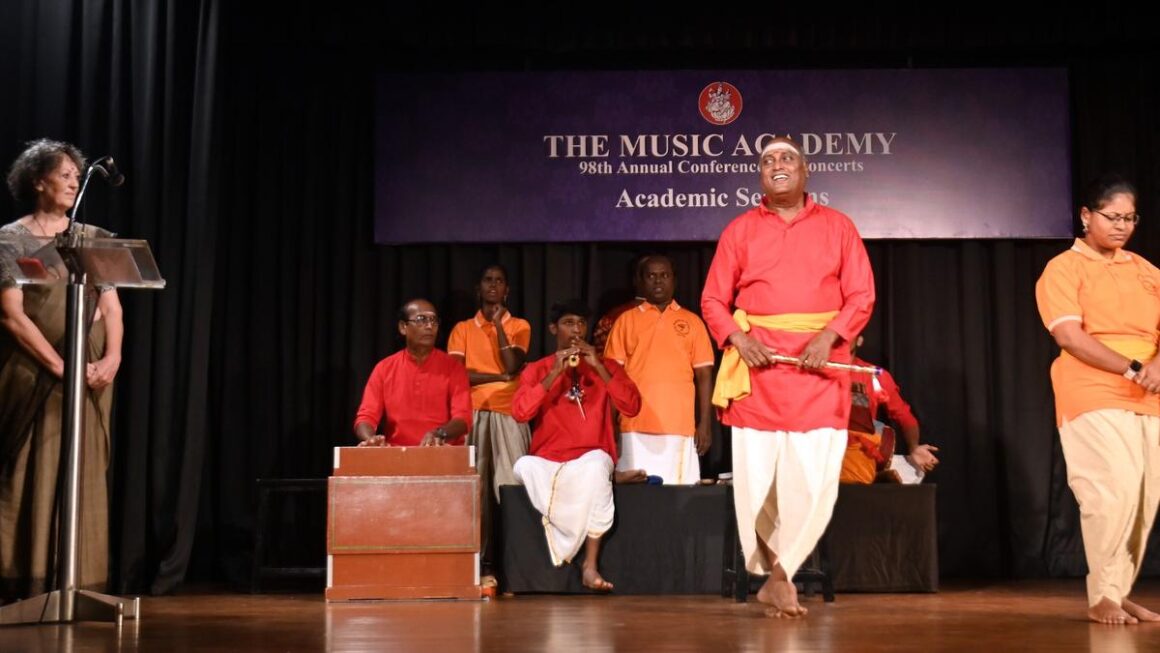

Day four of the lec dems at The Music Academy featured two interesting topics. The first, on the topic ‘Kuttu Raga-s : Evoking the character’ presented by vidwan P. Rajagopal and Hanne M. de Bruin, began with an unamplified musical performance by P. Rajagopal and his ensemble, featuring Vijayan on the harmonium, Sasikumar on the mukhaveena, and Selvakumar on the mridangam and dholak. The absence of amplification emphasised the natural and emotional depth of the art form. Hanne provided insights while Rajagopal demonstrated various aspects of Kattai Koothu, a traditional art form combining dance, drama, and storytelling.

Kattai Koothu performances are unamplified, requiring a high vocal range, particularly for male performers singing at the pitch of F#, considered very high today. This practice harks back to an older, unamplified era, lending the art form a unique timbre that conveys emotion more naturally. Performances often last through the night, spanning over eight hours, with storylines rooted in Indian mythological epics such as The Mahabharata. Historically performed only by men, women have recently begun participating in the performances. Hanne highlighted how practitioners, traditionally from marginalised communities, were often overlooked by the privileged urban elite.

One of the key rasas (emotions) expressed in Koothu is Veera (heroism), often showcased through raga Mohanam. Rajagopal enacted a scene from Hiranyavilasam, depicting Hiranyakashipu’s boastful proclamation of his glory. In Koothu, the dialogues are sung, merging seamlessly with the music to create a unified narrative reminiscent of a musical. Hanne explained how Koothu’s adaptability evolved as a response to social hierarchies, incorporating colloquial dialects into epic narratives for greater audience relatability. Rajagopal demonstrated a humorous scene between Krishna and Subhadra from The Mahabharata, showcasing the art form’s flexibility in infusing traditional stories with modern slang and humour.

The structure of Koothu songs typically involves two lines repeated by the chorus, followed by rhythmic or dance interludes. The melodies, often simple and repetitive like namavalis, are rooted in Carnatic music but bear the distinctive aesthetic of Koothu. Common ragas such as Kaanada, Kambhoji, Mohanam and Sindhubhairavi were identifiable from the demonstrations, but infused with the unique Koothu sound, as noted by Sangita Kalanidhi designee T.M. Krishna during his summation. Krishna also emphasised the need to keep the ragas as they are in each art form and not try and tamper with them under the pretext of cleansing it.

Another fascinating element was the concept of ‘Thiraipravesham’, demonstrated by Rajagopal through Karnan’s introduction in’’ The Mahabharata’s Kurukshetra war. In this technique, a translucent curtain initially reveals only the character’s head, with the accompanying text/dialogues highlighting the character’s traits. The curtain is then removed to fully unveil the character, creating a dramatic effect.

The expert committee discussed the adaptability of ragas in character representation and reflected on the mukhaveena, once a temple instrument, now eclipsed by the clarinet. Sasikumar expressed his dream of reviving the mukhaveena and passing on his knowledge to future generations. Rajagopal emphasised the lack of formal training structure in Koothu, fearing its essence might be diluted by rigid syllabuses. Krishna elaborated on the distinction between community art and organised art, advocating for minimal use of the term “folk.” The session concluded with an interactive performance by Rajagopal and Krishna, exploring the nuances of word-splitting in Carnatic and Koothu music while preserving melodic integrity.

This lecture-demonstration offered a deep dive into the intricate artistry of Kattai Koothu, blending scholarly insights with vibrant performances to highlight its cultural and musical significance.

‘Between Page and Stage: Raga and Raga Music in Classical Literary Sources’ by Naresh Keerthi

| Photo Credit:

K. Pichumani

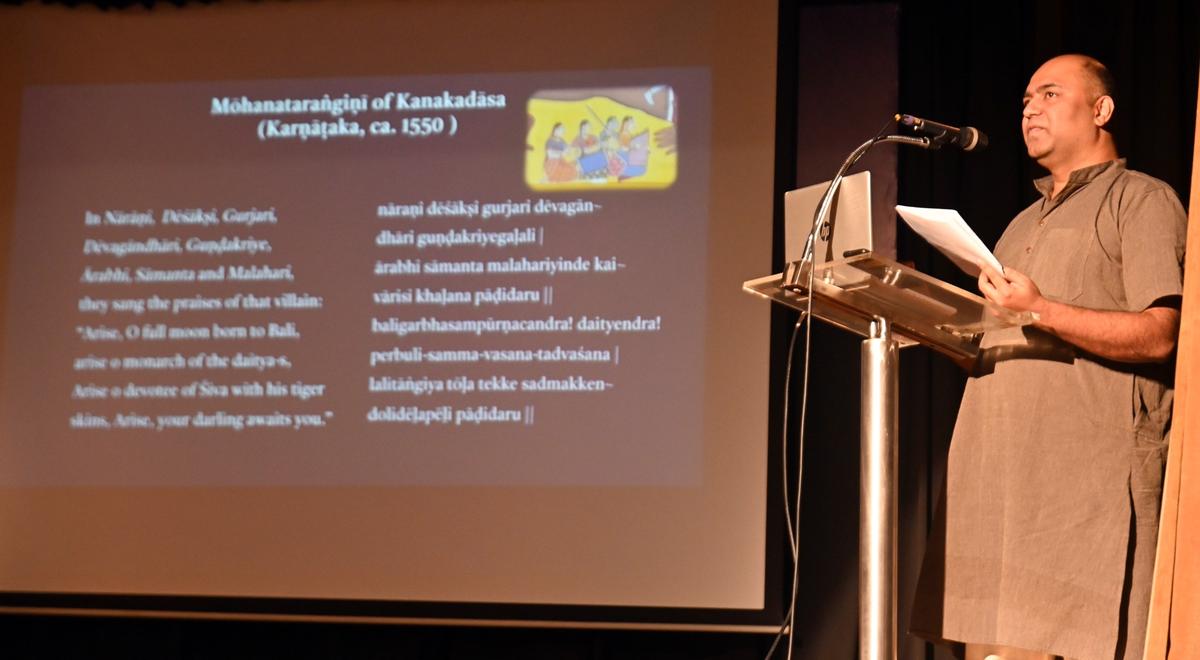

The second lecture demonstration of the day, titled ‘Between page and stage: Raga and raga music in classical literary sources’ by Naresh Keerthi, captivated the audience with its meticulous exploration of raga descriptions in literary works spanning from the 13th to the 17th centuries. Naresh highlighted how these texts provide detailed insights into the characteristics of ragas, enriching our understanding of early music traditions.

The session began with the ‘Vijayasrinatika’ by Rajaguru Mandana from 13th-century Malwa. This work described the raga Hindola as lacking the dhaivatham and exhibiting a kampita movement on the shadja and panchama. It was also identified as a ‘grama’ raga.

Naresh then discussed Terakanambi Bommarasa’s Sanatkumaracarite from Karnataka (1485). A notable story from this work describes a woman playing the mridangam while another apsara woman dances through several talas, including the seven suladi talas. One significant verse mentions ragas such as Dhanyasi, Malahari, Lalite, and Kambhoji, portraying their brilliance in performance.

The next focus was on Cokkanathacharitamu by Tiruvengalaraju (circa 1540), a story of the Thiruvilayadal. The singer Hemanatha boldly proclaims his musical prowess before the Pandya king. This text references gitas and prabandhas, with a line stating, “Gita prabandhamulu nanuvoppa mantra mandhyama taarakulam paade,” signifying the singing of these forms across all three octaves. The work also mentions ragas such as Arabhi, Gurjari, Samanta (a now-forgotten raga), and Devagandhari.

Naresh’s discussion of the Nalacharithamu Kavya (1600) by Raghunathanayaka left the audience in awe. While describing raga Nattai, the text details the glide of Ri into Sa as seen in the lines “durini shadjambu pondu padanga migula sarigama sarigama padanisa kramamu…” and Damayanti’s rendition of raga Gowla, where the rishabam “hugs” the shadja. These elements resonate with contemporary Carnatic practices. Additionally, the text describes the raga Jayantiseni as incorporating the dhaivatham of Gowla, close to the panchamam, and employing kampita gamaka on the madhyamam during descent.

The Raghunathavilasanatakam by Yajnanarayana Dikshithar further illuminated the characteristics of Nattai. The protagonist, Raghunatha, describes the raga’s characteristics: the dhaivatham and rishabam in the satshruti position, the nishadham as kakali, and the gandhara as antara. These elaborate descriptions highlighted the period’s increasing focus on raga’s stylistic nuances.

Naresh emphasised that early modern literary works often provided more elaborate and technical raga descriptions, reflecting the growing popularity and evolution of the song genre. Innovations such as new ragas emerged prominently during this period.

The expert committee’s discussion enriched the session further. Vidushi R.S. Jayalakshmi referenced mentions of music in the Silapathikaram from the 2nd century, while vidwan R.K. Shriramkumar highlighted the grama raga system’s mention in the Saundarya Lahari. Krishna concluded the session by cautioning against interpreting these literary raga descriptions solely through a scalar lens. He also cited a verse by Bhattumurthy describing raga Vasantha as having panchamam and noted how Subbarama Dikshithar incorporated the description in his Sampradaya Pradarshini, underscoring the continuity of musical thought.

Published – December 20, 2024 04:44 pm IST

Leave a Reply