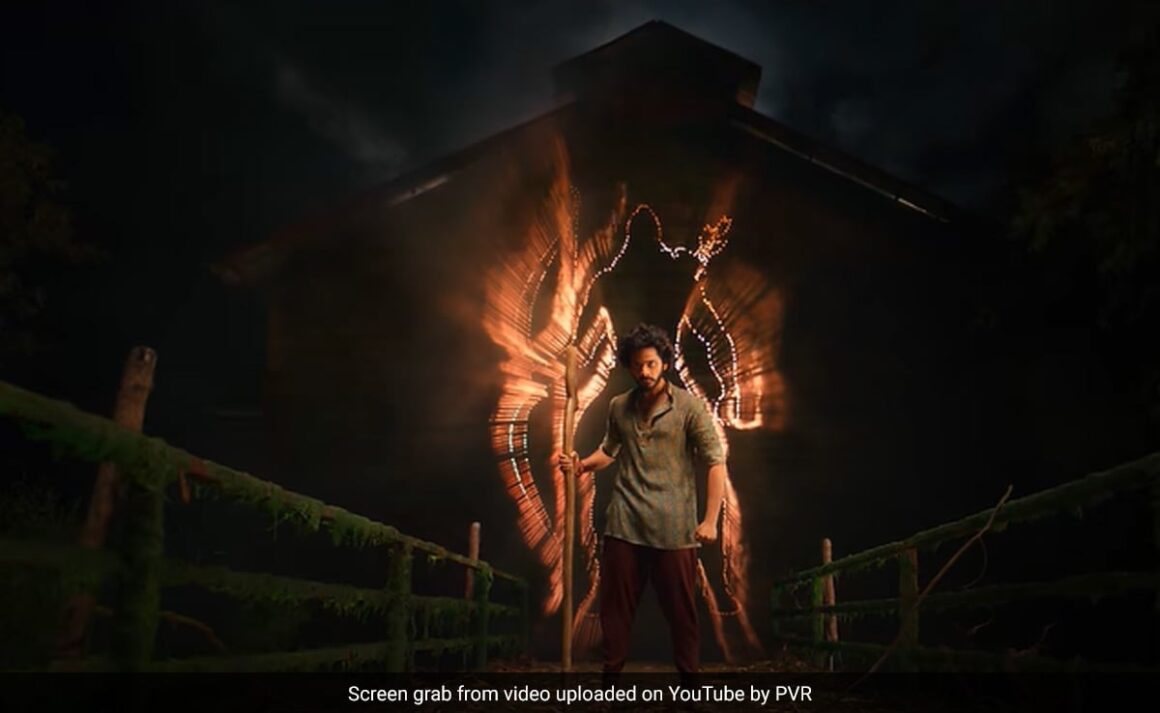

Prasanth Varma’s Hanu-Man, touted as the first Telugu-language superhero movie, scores in terms of scale and ambition. The execution, notwithstanding a few visual and ideational highs (most of them CGI-driven), struggles at times to keep pace what the film’s racing inner pulse. The disconnect mercifully isn’t overly glaring.

At the level of the yarn that Varma’s screenplay spins, Hanu-Man is a blend of the mythic and the mundane, the bombastic and the blithe. The film constantly flits from the epic to the everyday as it presents the coming-of-age story of an ordinary village boy who one fine day acquires Hanuman-like strength.

The first hour or so of the 158-minute movie is devoted to setting the stage for the grand transition – the man’s extraordinary leap into the league of superheroes as the world knows them. It is only after 40 minutes of meandering through his light-hearted shenanigans and comic misadventures that Hanu-Man reaches the point from where the essential classic confrontation between good and evil can begin.

The hyper-energetic Hanu-Man repackages superhero movie tropes within the cliched parameters of a overtly religion-centric drama designed to yield loads of action, doses of emotions, a whole lot of mirth and some devotional ardour.

That the screenplay never pauses to give the overheated structure some breathing space and that the lead actor Teja Sajja allows himself to be swept along by his larger-than-life pivotal role is both a strength and a drawback.

As Hanu-Man, written by the director himself, hurtles towards its predictable business end, it manages to ensure that its core strengths offset its weaknesses. It certainly isn’t a thinking person’s mythological and as an indigenous superhero epic it isn’t particularly original.

Hanu-Man draws ideas heavily from episodes of the Ramayana and proceeds to superficially touch upon the contemporary themes of power, rural exploitation, democracy and corporate expansion at the expense of the indigenous populations.

The film reunites the director with his Zombie Reddy star and builds a launchpad for a Prasanth Varma Cinematic Universe. By the time it ends, it drops enough hints about what its future might hold. On the evidence currently available, it isn’t like to put Baahubali or RRR in the shade.

For Hanu-Man to spawn an enduring and worthwhile set of sequels, it would have to appreciably raise its game. That would call for an infinitely bigger budget and that, in turn, will depend upon how enthusiastically the first outing is received by the target audience.

The Hindi dub of Hanu-Man of which this piece is a review, certainly needed greater consistency. It is overly droll and frequently strays into gratuitous slapstick as it follows a likeable but unruly village lad who after wasting his growing-up years in petty thievery and aimless drifting develops the urge to mend his ways and be of use to his community.

It is only accidentally that he acquires invincibility thanks to a pearl that he finds in the depths of a huge lake. But harnessing and sustaining his superpower and measuring up to the responsibility it bestows takes some doing. The man faces several obstacles. He does his best to overcome the hurdles because he has one major incentive in the form of a girl he has crush on.

But that isn’t where Hanu-Man begins. It opens in late 1990s Saurashtra where a young schoolboy named Michael (who grows up to a strapping man played by Vinay Rai) wants to be a superhero like Spiderman and Batman.

Michael’s parents prove to be a hindrance. So, he does what he thinks is best. A few years later, he teams up with an asthmatic scientist Siri (Vennela Kishore) to fulfil his dream to be strong enough to brush aside all opposition.

Cut to a remote village named Anjanadri. It is surrounded by hills, lakes and jungles. A giant statue of Lord Hanuman stands guard over the hamlet. The villagers here are at the mercy of a villainous wrestler, Gajapathi (Raj Deepak Shetty), and his brutal henchmen who force everyone to pay them protection money. Anybody who opposes their writ is mercilessly snuffed out by Gajapathi in the wrestling pit.

Anjanadri is badly in need of a saviour who can rid it of its tormentors. Hanumanthu (Teja Sajja), who lives with his stern elder sister Anjamma (Varalaxmi Sarathkumar), does not have the makings of one. When the school headmaster’s granddaughter Meenakshi (Amritha Aiyer), a doctor, returns to the village from the city, Hanumanthu wants to rekindle their childhood friendship and win her heart.

All his attempts to impress the girl boomerang. He nearly loses his life when bandits attack the village and he springs to Meenakshi’s defence. Hanumanthu is grievously injured and hurled into a lake. Life takes a new turn when he lies recuperating.

All the mythic iconography surrounding the strength that Hanuman possessed and his unquestioning loyalty to Lord Rama and his subjects is evoked all the way in this superhero actioner. With nothing to lose, Hanumanthu goes into messianic mode.

News of his exploits reach the city. Michael and his scientist-accomplice fly into Anjanadri on a helicopter and promise the villagers the moon in the name of corporate social responsibility.

Hanu-Man is two origin stories rolled into one. The evolution of Hanumanthu from an unassuming lover boy to a saviour of his people is one of them. The other is centered on Michael’s desperation to get his hands on whatever it is that gives Hanumanthu his special powers.

Hanu-Man owes an obvious debt to the Hollywood superhero flicks. It blends MCU and DC Comics excesses with the flights of the imagination that mythological tales of the Indian sub-continent facilitate.

The star aura that has developed around the likes of Rajinikanth, Mahesh Babu, Prabhas and Allu Arjun are alluded to in words and deed by Hanumanthu’s best friend, Kaasi (Getup Srinu), the village milkman who doubles up as the film’s all-weather comedian.

Does Hanu-Man possess the potential to sustain the universe that Prasanth Varma hopes to create? The jury is out. For the answer, we will have to wait until the proposed follow-up arrives in our midst next year.

Leave a Reply