New Delhi:

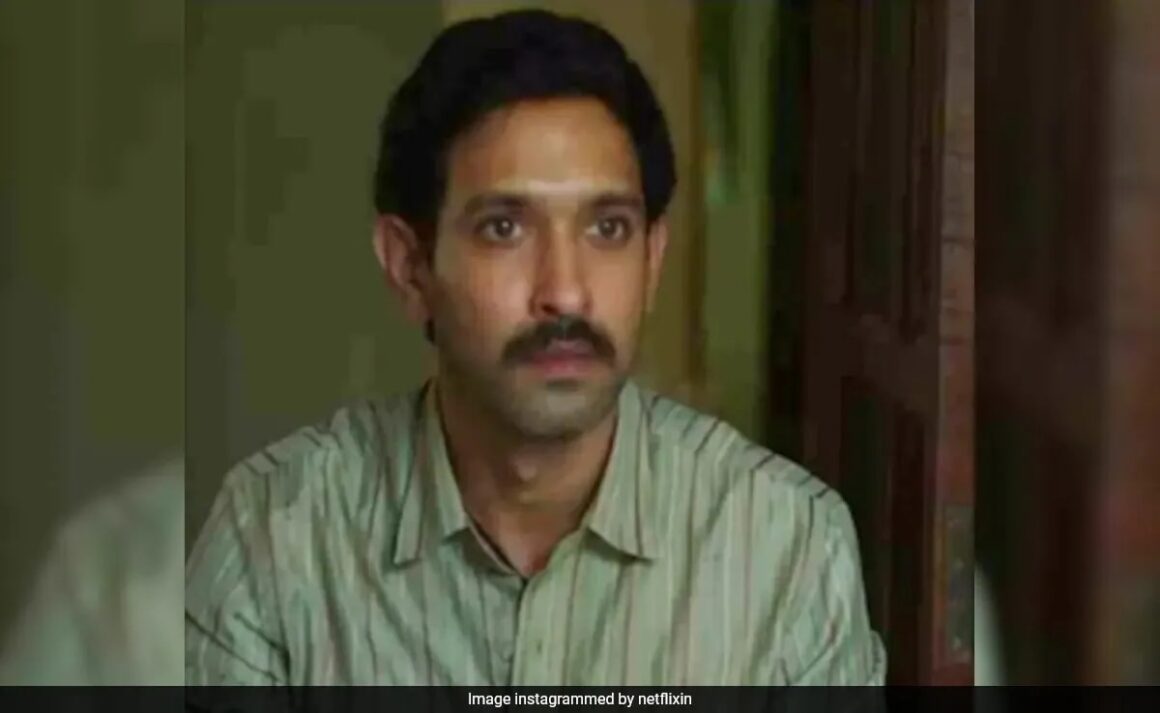

A portrait of a psychopath is never easy to pull off. Sector 36, inspired by the 2005-2006 Nithari killings, attempts the task without achieving much success. The film is never as searing or unsettling as one might expect it to be. There are multiple reasons for that. Directed by Aditya Nimbalkar and written by Bodhayan Roychaudhury, the Netflix film cites Newton’s third law of motion – every action has an equal and opposite reaction – to explain why Prem (Vikrant Massey), a businessman’s manservant who revels in the act of unbridled butchery, turned into the sort of fiend that he is.

As far as the basic characterisation goes, the creation of a context for inexplicable criminality is, as a narrative conceit, passable. But as a means for a deep-dive exploration of an unspeakably horrific series of murders committed over several months in a bungalow in a residential enclave of the city of New Delhi, it lacks the requisite sting.

By presenting a rationale for Prem’s killing of children of underprivileged migrants who live in a camp opposite the upmarket colony, the script softens the blow of the fictionalised reenactment of a true crime and prevents the perpetrator from becoming a truly and memorably chilling movie character.

Prem is a freak all right, a man completely inured to violence. He uses a meat cleaver to chop the bodies of the boys he sodomises and kills. Nor does he stop there. Cannibalism comes easy to him.

But if one were to meet him in the marketplace, he might be mistaken for an amiable, ever-smiling bloke incapable of hurting a fly. He has a wife and a daughter back in the village. Another child is on the way. But Prem is anything but a family man any child could be deemed to be safe with.

Riled by years of poverty and the affluence that he sees all around him, he is particularly miffed when participants muff up the chance to win big prize money on a prime-time television quiz show that he watches without fail. He obsesses about making it to the hot seat one day and claims he would return home with a hefty payout if he did.

Prem lives in and takes care of a bungalow that belongs to Karnal entrepreneur Balbir Singh Bassi (Akash Khurana), whose businesses are as multifarious as they are shady. He serves his master with unwavering loyalty. He lures the children of the slum into his dark lair and exploits them sexually before killing them and chopping them into little pieces to facilitate easy disposal of the remains.

Sector 36, produced by Jio Studios and Maddox Films, provides a brief backstory about a butcher-uncle in whose meat shop Prem worked and suffered as an orphan boy two decades ago. In light of what transpired there, the man believes what he does to the world is a fair reaction to what his uncle did unto him.

The “equal and opposite reaction” theory works more in the breach for Inspector Ram Charan Pandey (Deepak Dobriyal), son of a deceased Benaras Hindu University professor of mathematics and Sanskrit. He tries not to react to anything at all. That is his go-to defence mechanism.

Inspector Pandey heads a small police outpost that has only two other cops, plays Ravana in the local Ram Lila performance during Dussehra and speaks super chaste Hindi to the consternation of his boss, DCP Jawahar Rastogi (Darshan Jariwala).

The inspector manages to deal with the stranglehold of the ‘system’ by staying out of the crosshairs of his superiors and doing just enough policing to hold on to his job. He thrives on not rocking the boat.

But when the evil that Prem personifies hits home and his wife issues an ultimatum, Inspector Pandey decides that he has had enough. He sheds his apathy and gets cracking. He takes upon himself the task of solving the mystery of the disappearing children. That is easier said than done.

The investigative work of a reformed policeman out to nab a cold-blooded serial killer should have been the stuff of an edge-of-the-seat thriller. Sector 36 isn’t. It does not grip and bite. What is going on inside Prem’s bungalow – and his mind – is clear from the very outset.

The cop’s initially grudging and eventually full-blown response to the despairing cries of the hapless migrants whose children have vanished without a trace – and to the call of duty – constitutes the crux of the plot. Inspector Pandey faces impediments from his immediate superior, who retorts that IPS stands for “In Politicians’ Service”, and looks for ways to break the shackles.

When a new officer – Superintendent of Police Bhupen Saikia (Baharul Islam) – is transferred from a small-town to take charge of the Sector 36 police station, Pandey is given a free hand. But that isn’t the end of the story.

In a long confessional in which the killer spells out his modus operandi in graphic detail, Vikrant Massey grabs the opportunity to go all out with the monologue and hit the highest point of his performance. Prem brags and preens as he, among other terribly twisted things, smirkingly proffers a convenient reason for the killing of a teenage girl – the only victim of his who wasn’t a child.

Deepak Dobriyal, too, fills the screen with his shifty expressions of shock and bafflement as Prem makes a clean breast of diabolical misdeeds. But none of what the two actors transmit in the course of that protracted pivotal sequence delivers the desired punch in the gut.

The writing reduces the sequence to an encounter that borders on the droll and tends to make light of the heinous acts of a despicable deviant. The fault, therefore, obviously lies much more with the script than with the actors.

Massey’s interpretation of the psychotic Prem vacillates between the macabre and the mirthful. One behavioural trait that the character is given is a croaky cackle that he breaks into when he thinks he has cracked a joke or stumbles upon something that amuses him.

Humour is a rather odd choice here, especially because it just isn’t dark enough. The same lax, tongue-in-cheek tenor afflicts the character that Dobriyal essays. The situations that Inspector Pandey finds himself in and the quips that he makes are frequently out of step with the grave subject matter of the film.

He is by no means the sole offender in a film that is too haywire to be a hard-hitting chronicle of a crime hard to wrap one’s head around.

Leave a Reply