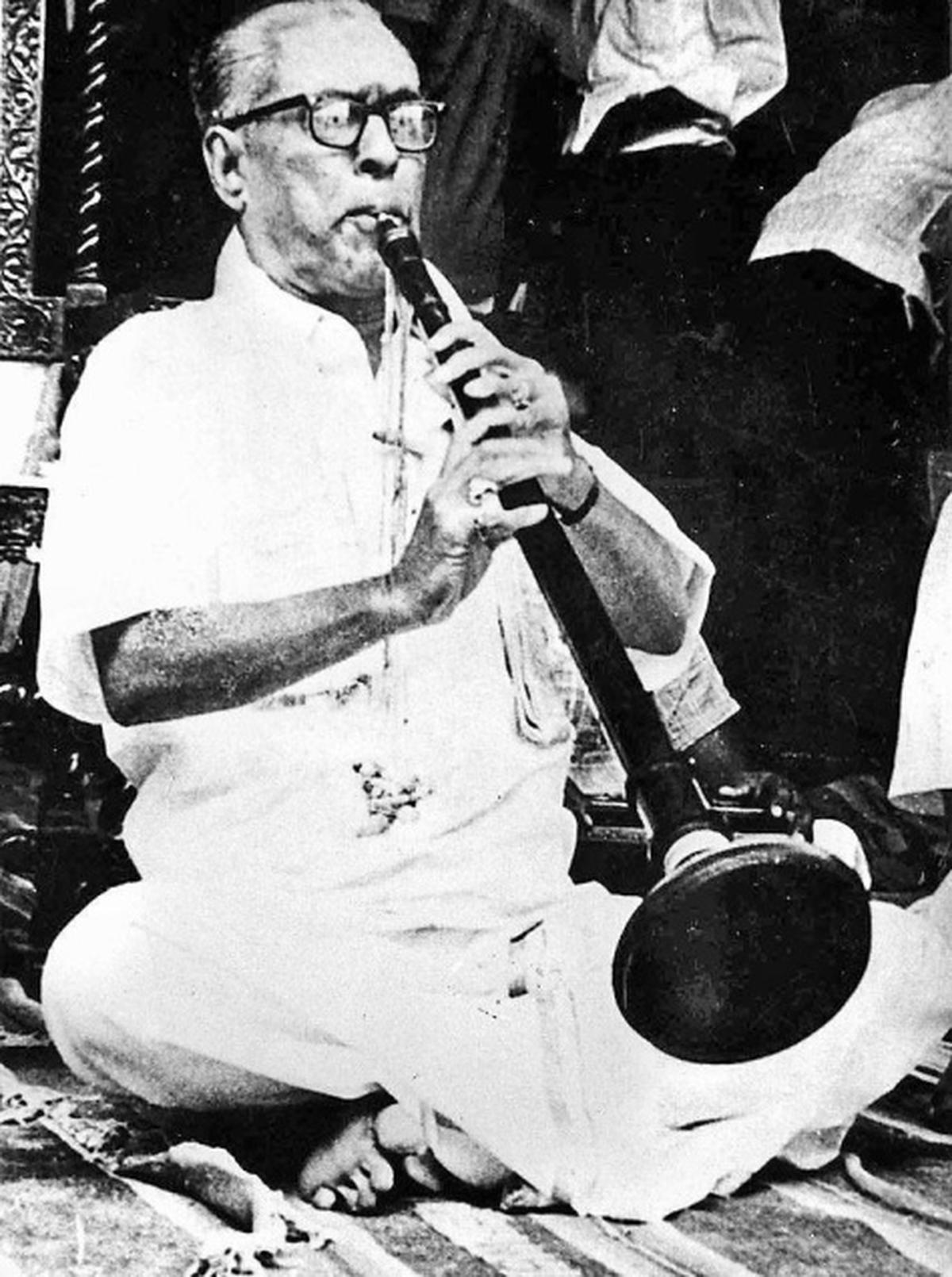

Nagaswaram vidwan Vedaranyam Vedamurthy.

| Photo Credit: Illustration: Saai

If one were to make a list of all-time great nagaswaram artistes, centenarian Vedaranyam Vedamurthy’s name is certain to make it to that list. Born on September 10, 1924, and having lived only 38 years, Vedamurthy etched his name permanently through his significantly modified instrument and its unique tone. He adopted a style, which was based on serenity and subtlety.

Vedamurthy’s life is well-documented in works such as B.M. Sundaram’s monumental Mangala Isai Mannargal. His maternal grandfather was the multifaceted genius Ammachatram Kannusami Pillai, under whom nagaswaram exponent T.N. Rajaratnam Pillai honed his skill. Vedamurthy had his training, both in vocal and nagaswaram, under Kannusami’s son A.K. Ganesa Pillai.

As a youngster, Vedamurthy had acted and sung in a few films including Thayumanavar, which had M.M. Dandapani Desikar in the lead role.

| Audio Credit: Courtesy: Lalitharam

Interestingly, Vedamurthy is one of the first names that come to mind when talking about sweetness in the nagaswaram’s tonal quality. Yet, all accounts point out that he was not naturally gifted with a sweet tone, and in his initial days, his style was more focused on displaying mastery over complex arithmetic patterns. It is also mentioned that he inserted a metallic extension in the nagaswaram, between the Ulavu (the pipe with seven holes to play the notes) and the Anasu (the conical section at the end), which resulted in getting a rich, ringing tone.

While it is true that Vedamurthy did modify the instrument, his efforts in doing so have been grossly undermined. Fortunately, the modified instrument is still preserved by his brother thavil maestro Vedaranyam Balasubramaniam. Upon examining it, a few key nuances have come to light.

| Audio Credit: Courtesy: Lalitharam

Modified tonal quality

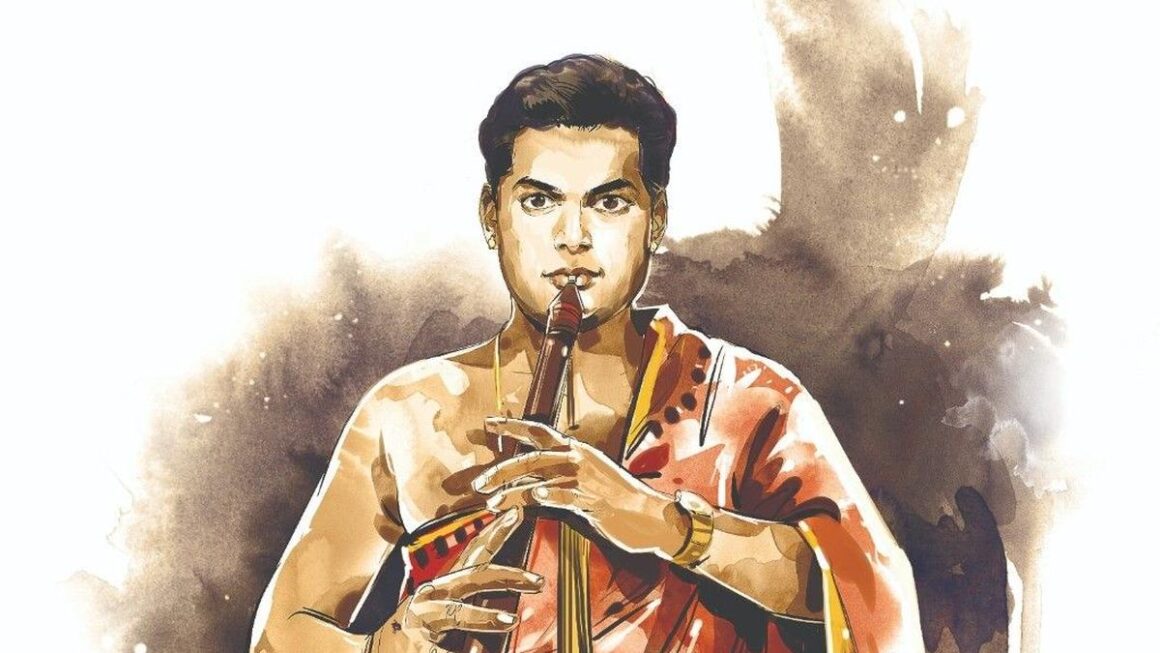

Tiruvengadu Subramania Pillai.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

According to Balasubramaniam, the original instrument was a gift from the nagaswaram legend Thiruvengadu Subramania Pillai, and its original pitch was in three kattai (scale). While the metallic extension did bring the pitch down, it must be noted that the natural tonal pitch of the modified instrument was much higher than the one that we hear in the recordings (about 1.5 kattai). The pitch of the double reeds (Seevali), attached to the nagaswaram for blowing, is neither the natural pitch of the modified instrument nor the pitch at which Vedamurthy used to play in his concerts. It is clear that the modifications that he made were not a ‘plug and play’ kind. Rather he had to compensate for the asynchrony with his blowing. It is with this insight that Vedamurthy’s conquest of attaining his desired tone needs to be appreciated.

It leads us to the question, why would an artiste bring in features that would create difficulty in playing an inherently finicky instrument? Unfortunately, we do not have first-hand sources to answer this. However, the handful of recordings that has cemented an undeniable place for Vedamurthy in the music world suggests that his significantly different ‘aesthetic choices’, when exploring ragas, could have nudged him towards the modifications, despite its limitations.

Entering the music world when T.N. Rajarathnam Pillai’s style was taking the entire Carnatic music world by storm, Vedamurthy’s choices were in total contrast. Unlike playing long drawn-out phrases and extensive elaborations on the higher octave, that projected the majesty of the instrument, Vedamurthy chose to paint his raga canvas with precise yet delicate notes. The meaningful pauses between his phrasings gave a mystic charm to his renderings. His elaborations were mostly in the middle register, only occasionally touching higher register notes without lingering on them. The recordings and song lists we have, though limited, indicate that his choice of ragas (e.g., Surutti, Nattaikurunji, Sahana, and Dhanyasi) fits his chosen style of playing.

Nagaswaram vidwan T.N. Rajaratnam Pillai took the Carnatic music world by storm with his unique style of playing.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

Jaarus on the nagaswaram

In veena, handling of jaarus – a type of gamakas produced through seamless sliding from a note to a relatively far note, result in the rounded sound effect as it enables the artistes to slide over the strings smoothly. But to produce the jaarus with the same effect on the nagaswaram can be quite challenging. Vedamurthy’s handling of such slides (for example the slide for Pa to Ri in Sahana) has led many to define his style as ‘playing veena on the nagaswaram’.

During his time, it was perhaps the norm that raga alapana took the centre stage. And even when played before a kriti, the focus was on exploring the raga and not really keeping the chosen kriti as a central theme for the raga exposition. Vedamurthy differed in this aspect too. His approach was unique and there was a sense of balance and connection in the duration of the raga alapana as well as the content of the exposition, with respect to the kriti that followed. His adherence to an unhurried approach was also seen in the choice of slower than usual kalapramanam (tempo) for several of the pieces not just in kritis, but also in javalis and Tiruppugazh.

Vedamurthy introduced his modified instrument in 1952 at the Arunagirinathar festival in Tiruchi. His career, with this instrument, lasted for slightly less than a decade. Probably, less than 20 hours of his recorded music is in circulation. But, there is more than enough sparkle in those recordings to keep his name afloat among the greatest even after six decades of his passing away.

Published – September 20, 2024 12:10 pm IST

Leave a Reply